Some have asked for an update on our worm farm. Several months ago, we bought some worms to help with composting and to use as bait for fishing. Our worms help reduce the amount of garbage we were previously simply sending to the local landfill. If all goes well, someday we may resell them, once we learn about the ins and outs of the inevitable rules and regulations.

Circle of life

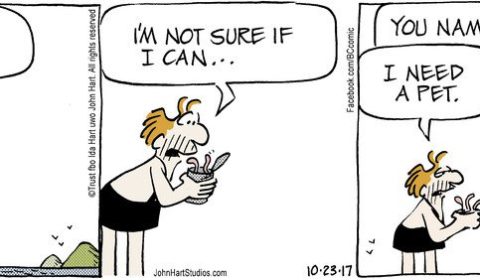

The chickens take an avid and ongoing interest in our worm farm.

We feed our worms the food scraps we do not feed the chickens. They consume them and reward us with odor-free, rich compost for greenhouse and garden use.

The chickens would very much like to participate in this circle of life, preferably by eating the worms. In fact, two of our hens actually broke into the container when we first got them.

However, we have since imposed more rigorous security. The result? I am happy to say that we are, in fact, smarter than our chickens, at least for now.

Breeds

We have two kinds of worms: red composting worms (also known as manure worms) and Alabama jumpers. The jumpers, which are actually originally from Asia, are primarily bait, though they do a great job at composting.

Both have done so well in their self-contained Colorado habitat, we thought we’d give them a try down South when we traveled to our place on Fowl River in Alabama.

Initial results

The worms are thriving. We’ve estimated they’ve doubled from 3,000 in number to at least 6,000.

When we loaded them up to bring to Alabama, we were careful to ensure secure transport. Read on to see why that is important.

Learning curve

There are two concerns we are exploring with our worms. Ironically, one is related to whether they can survive and thrive and the other to what happens if they survive and thrive to an invasive degree.

Temperature sensitivity

The first hypothesis is that they cannot survive temperatures under 60 degrees on a sustained basis. We keep them in an isolated, climate controlled, enclosed container in a heated indoor area.

However, throughout this first autumn, they *have* been in temperatures in the 50s and 60s for months at a time and have survived without incident. They have reproduced in such an impressive number, in fact, that we feel confident they can handle those temperatures.

Non-native species

Sustainable farming apply even to vermiculture. We respect the balance of nature and, even though it seems odd to give such thought to something as basic as an earthworm, they are not native to large swaths of the northern United States.

Which brings us to the second concern. People are studying whether “exotic earthworms” such as the Alabama jumpers present issues as an invasive species, particularly in the Smoky Mountains and the forests in, among other northern areas, Wisconsin.

([From wildflower.org:]) BioScience V. 52, no. 9, pp. 801-811) say: “Earthworms species from northern latitudes (e.g., European lumbricids and some Asian megascolecids) are poor colonizers in tropical or subtropical climates (except in localized temperate situations), and vice versa. For example, despite continued and widespread introduction throughout the United States, Eisenia fetida, the lumbricid ‘manure worm’ commonly used in vermicomposting, is not often found in natural habitats in the southern United States.” So, unless your worm bin is situated in an area with lots of leaf litter and/or soil high in organic matter, any escapees from the bin should not be a serious problem.

So, the data seems mixed. Though they eat the leaf cover in some forested areas, local beetles eat them. Per wildflower.org, there is no data that says they’ve ever established a sustained presence anywhere they should not be.

Because we do care about the environment, however, we continue to monitor the research.

Secure your worms!

So, a note about worm security (now there’s a phrase I never thought I’d write:) out of an abundance of caution, we are vigilant about inadvertently letting any escape. We secure them when we transport them, including their cocoons. We are not yet using them in our southern gardens and we may choose not to at all, or to only use the red wigglers.

Alabama jumpers cannot inhabit the Colorado Rocky Mountains where we live because

- the soil is inhospitable and

- they cannot consistently survive the sustained hard freezes so common during our winters.

Summary

We take a careful and nethodical approach to each new thing we try at Big Dawg Farms. So, we will only be using worms in Colorado for compost inside our yet-to-be-constructed greenhouses. In Alabama, where earthworms are a long-time part of the ecosystem, we will use them for bait. Sustainable farming best practices apply even to – and especially to – something as basic as vermiculture.

Big Dawg Colorado Worm Farm – lessons so far